Nick Dover is a familiar face.

Anyone with meaningful time at QLI can spot the long-time resident’s broad silhouette; can describe his hurried, always-getting-somewhere walk; can pick out his big, booming voice from a crowd.

They could probably tell you, too, about the way Dover busies himself, about a work ethic that, by all appearances, sustains itself in perpetuity. He’s an early riser, someone who’d work twenty hours straight all seven days of the week if he didn’t have to stop for food or rest.

A person might tell you about Dover’s travels, about his almost nomadic sensibility. A restlessness, as if being home for too long was itself a kind of bad omen. There were many travels, indeed, almost too many to count—long voyages by SUV down the length of Missouri or snaking through the lonely passes of the South Dakota Badlands. He’d return to QLI with stories of setting camp out in all that wild. Alone, but happy. Independent and free.

Those who know Dover best might not mention any of this. They might instead choose to describe him by his personality—how he strikes a brusque impression on first blush but is more appropriately defined by his willingness to bend backward for those in need.

In the years before the pandemic, he was a common fixture of the QLI’s Lied Life Center—planning Sunday morning brunches or summer evening grillouts for appreciative client families.

It’s here where the real Nick Dover exists. A place between the hard work and the generosity, where he can mold fragile spirits into resilient things with an understanding conversation or over a warm meal.

It’s here where Nick Dover has, after injury, defined his own identity.

—

In 2008, nothing about Nick Dover’s life seemed simple.

The then-33-year-old had only barely survived traumatic head injuries after an accident on a Central Nebraska feedlot. He spent nearly forty days in intensive hospital care and transferred to a skilled nursing facility before eventually finding admission into QLI’s rehabilitation program.

It was a distressing, disorienting period. He had only known independence in his adult life. By 15, he’d moved away from his childhood home. By 18, he’d successfully completed high school despite living on his own. In his twenties and early thirties, he earned a college degree and built a career working with livestock on cattle ranches, living a life he had authored with relative autonomy.

Of the accident, all he could summon were stories passed along told by coworkers, family members, and medical staff hoping to explain the new reality in which he found himself.

As a result, the sudden necessity for constant hands-on support prompted only resistance.

“I was liable to blow up like a stick of dynamite,” Dover says. “I didn’t understand why I was at QLI or how much help I needed.”

Dover describes the early days at QLI as if looking back on another person’s life altogether. Angry, confused, and prone to abrupt changes in temperament, he struggled to find stable motivation to participate in the center’s custom-tailored rehabilitation program. Rather than butt heads with another therapist or spend yet another hour in seemingly fruitess cognitive training, he sought out quiet spaces, withdrawing inward.

“I knew this campus pretty well,” he says. “I knew the places where I could go and hide. If you knew where to look you’d find me covered up in a closet, sleeping.”

Getting any rehabilitation programming to stick required Dover’s complete buy-in, implicit trust in the team to not only keep his best interests in focus, but to further his pursuit of his own goals—including, in Dover’s mind, a return to the workforce.

And that necessitated a different tack entirely.

“In the beginning, we had to step back with Nick and slow him down,” says Mel Mixan, QLI’s Coordinator of Life Path Services for the company’s long-term campus. During Dover’s program, Mixan served as a leader on the rehabilitation team, responsible for uncovering a sense of purpose in clients and interweaving it into the varying arms of their clinical itineraries.

“We spent six months just opening those doors, building trust, getting to know why he got out of bed every day. He was very work-focused—his goal was always to get back to work. The things he really liked, like fishing and camping and nature, none of that really mattered to him if he couldn’t work. That was core to his identity.”

The rehabilitation team converted this momentum, turning his therapy assessments and training sessions into a nominal agenda, utilizing therapy staff as ostensible supervisors. All of this operating under the agreed-upon expectation that Dover would make appointments and perform to the best of his ability, as though he were an employee reporting to an established employer.

It was a clever pivot. And the rigidity of the plan seemed to work. It allowed for scaled difficulty, harder or easier, depending on his progress. But he was participating. And that was as good a square one as the team could have hoped for.

In that role, a switch flipped. Dover discovered what he describes as a second lease on life.

“I realized being a volunteer gave me a greater sense of purpose,” he says. “It kept me busy, but it mostly helped me avoid valleys of emotional lows.”

Volunteering filled the void left by his desire to work. Beyond his time at the Food Bank, Dover found ways to slot himself into the goings-on around QLI. He lent help fishing or with off-campus camping retreats and partnered with the clinical team to reveal the purpose and passion of incoming brain injury survivors—just as the Life Path Services team had done for him.

He found a knack for seeing through the hurt and vulnerability of injury. He could sit down with someone mired in gloom and be a kindred spirit or a motivating voice.

His talent proved to be an important tool.

“If I saw someone struggling, I knew I could give them my time,” Dover says.

“People can be like closed flowers. But if you nurture them and spend the effort to understand them, they can blossom. They can open up. And that was easy for me to do when I could say, ‘Hey, I’ve been in your shoes.’”

As Dover’s commitment benefited others, so too was he experiencing gains in his own right.

Less than a year after his injury, Dover graduated from QLI’s intensive rehabilitation program to live in the on-campus Lied Assisted Living Apartment complex, enjoying relative residential independence while still utilizing QLI’s resources to meet medical needs and continue developing the next phases of his life path.

“The move to assisted living was really a bridge to something bigger for Nick,” says Mixan, who remained involved in Dover’s efforts to build important life skills.

“We still structured his day to resemble a work schedule, but a lot of the work at that point focused on things like life management—maintaining a budget, finding new things that stoked his passions, really just taking advantage of the fact that he still needed QLI for support as he rediscovered his identity.”

Shortly after his transition to a permanent living space within QLI, Dover was introduced to a new interest, one with enormous implications on his future.

“I think the kitchen staff was smoking pork butts for the residents,” he says. “They asked me to help. I really liked it. Just learning about how many different ways you could prep the meat—that intrigued me.”

He smiles telling the story. It’s clear to him now, just as it was in that simple moment, that his desire to impact people, even to propel them toward some greater achievement, could intersect with this newfound interest in cooking.

QLI’s team recognized this, too.

From huge barbecue nights to chili cook-offs to simple weekend sit-downs for travel-weary families, Dover earned his reputation as a culinary wizard.

In some ways, cooking became central to his identity. Certainly, it served as the pillar of his approach to creating comfort for new rehabilitation admits. But in 2018, some ten years after his injury, he began thinking bigger—about the ways cooking and empathy could serve a greater cause.

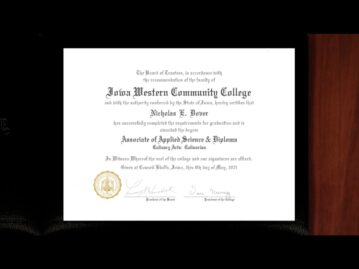

The line of thought landed Dover on a return trip to college study. Working closely with advisors at Iowa Western Community College, Dover enrolled in the school’s culinary arts program.

Reentry into academia wasn’t easy. For that reason, he kept school advisors close and instructors closer, commonly spending time in out-of-class meetings to reiterate concepts or redemonstrate techniques. His days ran long, sometimes 15 hours or more entrenched in deep study.

But the hard work created tangible returns. He managed a strong grade-point average, was the subject of adulation from peers and instructors alike, and received top honors at the college’s 10th Annual Legion Riders Chili Cookoff.

If there had been any doubt that he’d found his way, Dover himself had erased it.

He tells a story from the chili cookoff, a moment he looks back on as a kind of affirmation—proof positive that his big heart and culinary passion can touch lives.

“During the competition, I had this elderly guy come up,” Dover says. “He kind of had that down-and-out look about him, but he’d been to our table a couple times throughout the night, just talking to us. He finally came up to us with a bowl, instead of the cup most people used, and he asked to fill the bowl with chili. He told me our cinnamon rolls tasted just like his mom’s, and that he couldn’t get enough of the chili we’d made.

“I went and found a big bowl at the end of the night, filled it full with chili, saran-wrapped it, went and found him and told him to take the rest of our chili home. You could see his eyes open big and his shoulders lift. He was just so tickled.”

—

May 2021.

More than 13 years after the fateful accident on the feedlot. His was an injury so catastrophic, doctors couldn’t guarantee any hope for survival.

And, yet, here he is—the recipient of a new accolade, ready to step forward into a bold new chapter of life.

But it’s more, too. A springboard of possibility, a culmination of all his experience and passion propelling him into uncharted waters.

His journey to give back is only beginning. He speaks at length about a desire to share his knowledge—not only of cooking, but of budgeting, of time management, of conquering hardship through persistence and patience—with at-risk youth. He sees people as more than the sum of their problems. He knows firsthand how life can be defined by the good things, by the achievements and milestones, in a way that transcends tragedy.

The endeavor is, as he puts it, only the next of many adventures left to take. Only the next of many successes yet to earn.

“Anything Nick Dover is going to do with his future is going to be beautiful,” says Mixan. “He’s done so much just to prove to himself that he can. His story isn’t anywhere close to ending.”

Dover himself agrees. People around QLI know him for a lot of reasons. For his generosity and tireless energy, for his skill behind the griddle or over a grill flame. He’s ready for people to see so much more.

“My aunt would always say, ‘You put your mind to something and you can do it,’” he says.

“So put your mind to something you enjoy. For me, that’s the closure I feel when I know I’ve done something for someone else that will help them be stronger. For me, that’s where I find purpose.”

Categories: Brain Injury, Client Story